Dante the eternal

by Victoria Thomas

The moon is underneath our feet

Henceforth the time allotted us is brief.

-Dante Alghieri

It may seem unlikely that a 700-year-old epic poem from Florence which devotes one-third of its verses to the tortures of the Inferno could be considered a “commedia.” And although Dante Alighieri’s poem, called The Divine Comedy by English speakers, is no laugh-riot by modern standards, it was so named because it has a happy ending. Well, sort of.

Let’s start with actor Tom Hanks, novelist Dan Brown, and director Ron Howard. They’ve teamed on three major thrillers for the big screen, including the 2016 thriller, Inferno, which loosely refers to some elements of Dante’s work. Hanks’ character Robert Langdon has some rad cinematic hallucinations (a Plague Doctor in the classic beaked mask now seems prescient in our post-Covid world) which might have thrilled the poet with their vivid effects.

Love it or hate it, the glossy Hanks/Brown/Howard blockbuster is simply one more proof of Dante’s enduring allure. A generation earlier, director Martin Scorsese referenced reading Dante for what he described as a “descent into a modern urban hell” while making his surreal 1977 classic Taxi Driver. Two years later, director Frances Ford Coppola cited his childhood study of Dante, as well as his immersion in Italian Roman Catholic practice, as “near-death training” for his creation of the swampy, steamy, fever-dream Apocalypse Now in 1979, an experience he described as “hell on earth in every way.”

Perhaps the most familiar illustrations of Dante’s work are the trippy visions of fellow poet William Blake. Tchaikovsky and Liszt both took musical inspiration from the epic, as does Leonardo Frigo, a young multimedia artist who inscribes de-stringed violins (and occasionally cellos) with illustrations inspired by Dante’s Inferno. Born and raised in Asagio, Italy, now living in London, Soolip recently used Zoom for a lively trans-Atlantic interview, mezzo-mezzo alla Anglaise-Italiano, with the artist as he packed his studio to relocate. Frigo says, “Dante taught me how to dream, how to imagine.”

For those of us who may have partied hearty and slept in instead of acing that Ren Lit class back in the day, Dante lived two centuries before the start of the Protestant Reformation, from 1265 to 1321. He is beloved by Italians and others as the father of Italian literature, much as the way that English language scholars revere Geoffrey Chaucer, who began writing his rollicking Middle English tale about a century later.

An understanding of the religious landscape of medieval Italy enriches our reading of Dante. Although of course Dante was deeply embedded in Roman Catholic belief and culture, he boldly assailed the corruption of the Church. In this way, he provided a literary template for Chaucer, and surprisingly aligned Dante with the spirit of the 16th and 17th-century Protestants who followed. His outspokenness also earned him scorn and political exile.

A key complaint from Dante: simony, meaning the payola-like purchase and use of indulgences. A quick gloss: righteous Roman Catholics of the day were expected to follow a strict calendar of seasonal observances, including fasting and making other sacrifices at appointed times throughout the year. For example, during the 40-day fast of Lent, Catholics were expected to abstain from the pleasures of the flesh. This restriction referred to both bed and board, requiring the faithful to refrain from having sex, eating meat (fish being the loophole), eggs and cheese, cooking with fat and butter, and drinking alcohol.

So, the Church fathers shrewdly sold “indulgences,” which were basically a hall-pass to partake of forbidden pleasures, without leaving a black mark on your sacramental report-card, for a handsome fee. Cash payment, and a few laps around the beads, and Te absolvo, Go Forth and Sin No More. Many of the great edifices across Europe were said to have been built on butter, metaphorically speaking. And, in addition to the selling of indulgences, simony also included the opportunity to buy one’s way into a license to preach, as well as into a prestigious ecclesiastical post or office.

Human nature being what it is, was, and shall always be, the Church in its wisdom realized that people love to cheat.

Here's what Dante has to say on the matter:

Rapacious ones, who take the things of God,

that ought to be the brides of Righteousness,

and make them fornicate for gold and silver!

The time has come to let the trumpet sound

for you; ...

More bees in Dante’s bonnet: money-grubbing religious orders, the political machinations of the Papacy, and sexual hijinks among the supposedly chaste clergy. Chaucer may have addressed similar moral outrage with far more humor and wicked lewdness, but no other writer weighs in with moral authority to match that of Dante.

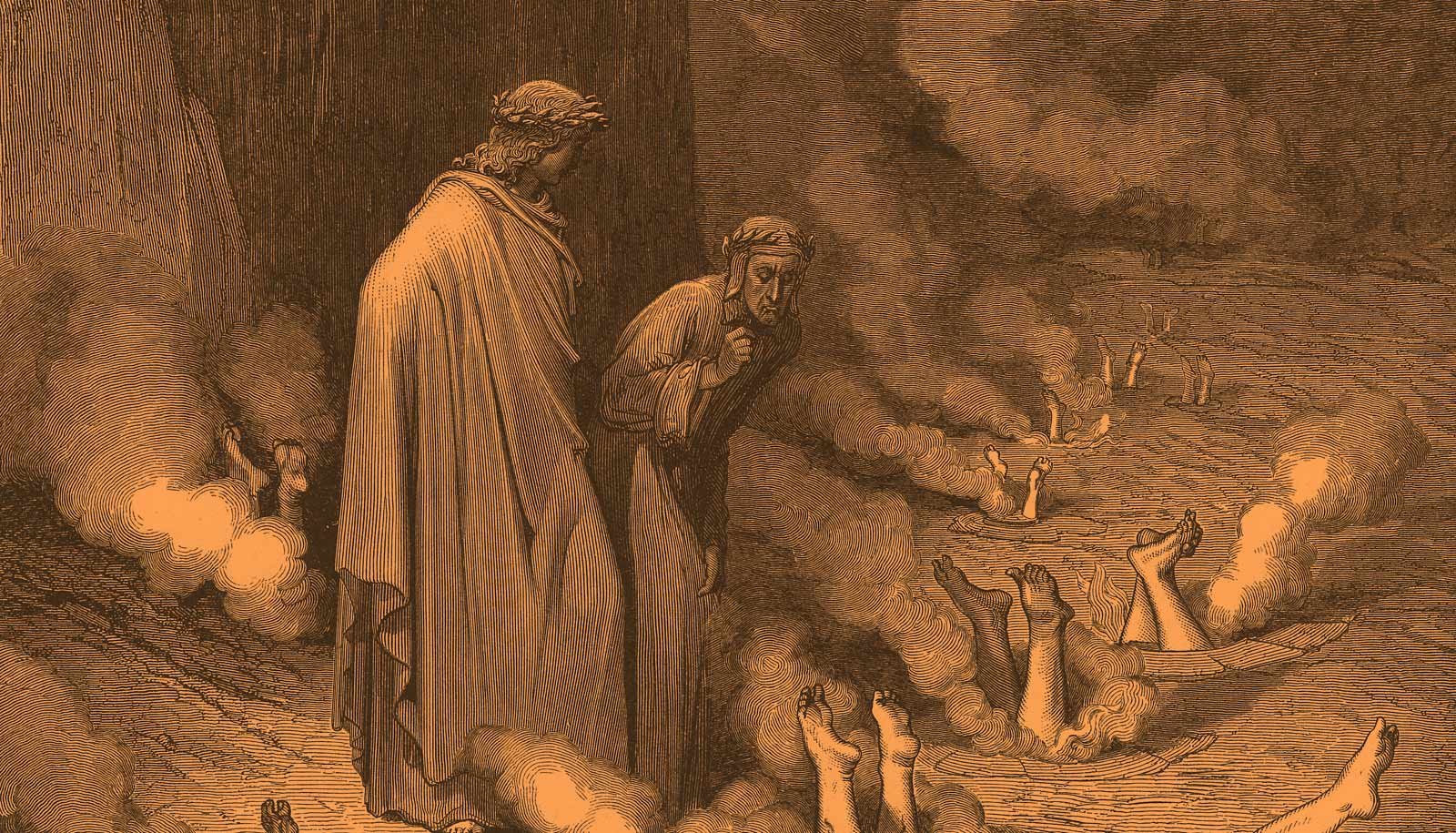

While newer iterations of Christian theology tend to downplay the existence of Limbo (which means “edge” in Latin), Purgatory and Hell, it seems likely that Dante believed these to actual locations as well as metaphors for aspects of the human experience. Dante’s Inferno was composed of nine levels, with the extremity of turpitude increasing as one descends. Visual artists of past centuries often depicted the Inferno as a kind of tiered birthday cake of torture, or a blueprint bearing an uncanny resemblance to the floor plan of any modern multi-level parking garage. The Roman poet Virgil appears by Dante’s side as a sort of hybrid security guard-valet, guiding the poet through this terrifying labyrinth as the bearer of supernatural GPS.

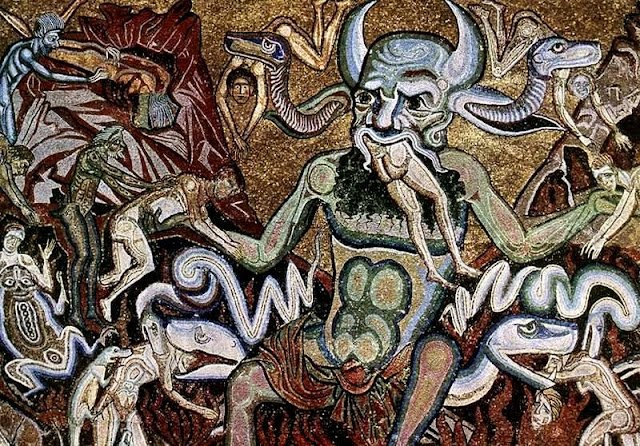

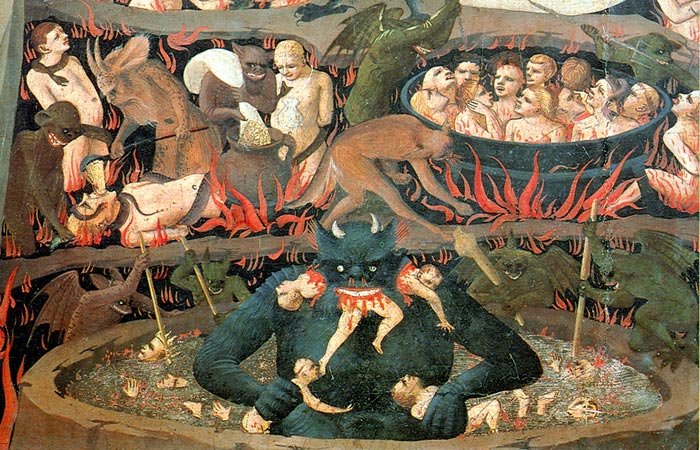

The punishments of the Inferno are divided into three sections, descending from the minor to the perhaps unforgivable. The top level belongs to mild offenders: virtuous but unbaptized pagans, along with impulsive gluttons and the lustful. The second tier is the realm of those who willfully refuse God. The third and most vile of the realms of hell is the domain of those who do harm to themselves or others by physical or deceptive means. Suicides are transformed into mangled, twisting, lamenting trees, while dictators and murderers boil in a river of blood. Liars and betrayers are submerged in bile, while blasphemers walk fiery sands. In an especially cruel twist, the ninth and lowest circle of Dante’s Underworld is the frozen lake Cocytus, where Satan, submerged waist-high in ice, eternally munches on the damned with three voracious mouths.

An aside: the aforementioned Church indulgences, when not being squandered on cocktails, creampuffs, and other naughty no-no’s, could also be pressed into service as negotiation chits to get a damned individual out of the Inferno. (This really cheesed off Dante, pardon the pun.)

The image which seemed to resonate most with medieval painters, as well as artists in other mediums, was the three-headed Satan gnawing on betrayers Judas, Brutus, and Cassius (the latter two assassinated Julius Caesar). Beneath each of his three chins, Satan flaps a pair of scaly wings which turn the frigid winds of Cocytus even more punishingly cold. Fra Angelico in his 1431 masterpiece The Last Judgment spared no gristly detail.

It’s telling that Dante opens his epic with the worst possible scenarios, and so it makes sense, too, that mild-mannered Frigo devoted five years to the Inferno. The time was spent covering the surface of 33 violins and 1 cello -- one instrument for each of the 34 Cantos -- primarily using a classic nib-pen and India Ink. “I make a secret recipe, so the inks don’t bleed into the wood,” he adds slyly.

Yet Frigo seems untroubled by his journey through the ghastly underworld. He arrived in London from Asagio in 2015 with an interest in improving his English, as well as serving his mission to share the genius of Italian culture and language worldwide. “Dante was present in my life as a child, he says. “Our mother would read Dante to us as a bedtime story. It was a book with illustrations, and I was 5 or 6 years old, and I instantly fell in love.” His love for the Florentine master deepened when Frigo moved to Venice at the age of 20. For the next three years, a massive statue of Dante in the campus quad became a daily presence in his life.

“As a child, I was always making drawings,” he remembers, “and I studied violin for a few years. At age 15, I took off the strings, removed the varnish, and painted my first violin.” The fate of his next six violins: what else? The Seven Deadly Sins became the theme the subject for his first installation.

After graduating, Frigo arrived In London with one suitcase and three violins and soon met a local globemaker who offered him studio space in exchange for learning to make museum-quality globes. “I got the space and the job, and I knew no one. I felt like Dante in exile, far from my country. In the loneliness, I would paint and talk to Dante.”

He created his installation as part of Italy’s massive celebration honoring the untimely death of the poet, probably from malaria, in Ravenna in 1321. And now a new question burns in Frigo’s brain: “Did Dante meet Marco Polo? If so, why didn’t Marco Polo tell Dante about China? Dante thought the world ended at the Ganges!”

It is a fact that the Comedy and The Travels of Marco Polo were written within a few years of each other, just a couple of miles apart. The men were peninsular neighbors and contemporaries. Both were expatriates for a good portion of their lives: Marco as an immigrant in the Mongol Empire in his twenties and thirties, and Dante in political exile from Florence for the last two decades of his life. Both spent the years of their expatriation on the move: Marco as the Great Khan’s envoy to many parts of the Empire and Dante as guest of various Italian courts. Yet only rarely are the two discussed side by side in scholarly literature.

Inspired by Renaissance priest, cosmographer and cartographer Vincenzo Coronelli of Venice, Frigo is now planning to create “…globes made in the 17th century way, illustrating Dante’s locations, the way he would have seen it. He thought Jerusalem was at the North Pole.”

Seven centuries after Dante’s stylus was set down for a final time, international organizations honoring Dante, both scholarly and popular in nature, continue to proliferate, further evidence that the world is obsessed. The poet’s name has even recently been used for a flashy new breed of audio and video connectivity software.

This obsession is, in the end, puzzling. Without taking an official count, church attendance -- certainly Roman Catholic church attendance-- is down. Words like “sin” occur less and less in casual conversation. And yet, many of us, like Dante, can honestly say:

Nello mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

Mi ritrovai per una selva oscura,

Che la diritta via era smarrita.

This haunting passage translates, “Here, in the middle of the road of this life, / I awakened in a dark wood, / And the straight path was lost.” A step away from the literal interpretation, Dante writes of the universal human experience: middle age, loss, disillusionment, temptation, unrequited love, and wistfully moving on.

Taping up boxes to load into a waiting truck, Frigo is leaving the studio that has been his home for 7 years. “Dante challenges us, you know,” he says, running his hands lightly over the body of a freshly whitewashed violin, plucked from a shuttered luthier’s shop. He will draw the design, incorporating ancient coats-of-arms, symbols, and maps of constellations, on paper first, then transfer it to the surface of the violin. He doesn’t use pencil on the instrument itself, just pen and ink on wood, then varnish. “This has been a big cleansing for me, this journey. You know, for the first three-and-a-half years, nobody believed in my project. People can be tough. So, I had faith and made a big sacrifice.”

Then he smiles. “You know,” he says, “Inside a normal violin that you use for playing, there is a little piece of wood inside, a little brace, what musicians call an anima. For the violins I use for the Inferno project, I take out the anima. Because in the Inferno, there is no anima.”

Because in Latin, “anima” means “soul.”

Following his hero on his archetypal magical mystery tour, Dante dares us to see with new eyes so that we may “Rebehold the stars.”

All images courtesy of the artist and Wikimedia Commons