The elemental rikki ducornet

by Victoria Thomas

If Rikki Ducornet didn’t already exist, the literary world would have to invent her. She’s the pomegranate in the formal banquet of women’s writing.

These days, most publishers and readers prefer something simple -- an apple, maybe -- to a pomegranate, which is botany’s high-maintenance prima donna. You can simply bite into an apple, or cut it into neat wedges for easy eating.

A pomegranate protects itself with a leathery shell, further protecting its jewel-like arils with internal warrens of bitter, white membrane. The precious juicy bits are actually seeds, sheathed in only the thinnest case of tart, garnet gloss. A pomegranate is sticky, the stain is indelible. In fact, like the author Ducornet, myths proliferate around the fruit. Some historians maintain that pomegranate juice was used to dye the fabulous rugs of ancient Persia. Some Biblical interpreters advise that the forbidden fruit of Genesis was not an apple, but a pomegranate, which, like a fig, will spontaneously burst open when ripe to display a luridly erotic, gemmy, jammy, purply-wet interior of promising fertility. And Rabbinic scholars inform us that the pomegranate, symbol of the Jewish New Year, contains 613 seeds, one for each mitzvah or commandment which the faithful are expected to observe throughout the year. The specific numeral is imperative since it reduces down to the One, the Almighty YHWH.

The above easily applies to Rikki Ducornet as well, spiritual in a floaty sort of way, deliberately mysterious, sticky, purply, clinging, erotic, difficult. She’s a piece of work that requires some trouble, a writer who would not have emerged in our current publishing era of the easy three-minute read. In the 1970s, Ducornet developed a huge collegiate following, especially among women English majors. And why not? With her raven’s wing of dark hair and sloe-eyes, she resembled a velvety, voluptuous, multi-ethnic blend of our favorite songstresses: Joan Baez, Laura Nyro, and even a spritz of early Cher. At this writing, Ducornet is now 80. Having lived all over the world, beginning with a childhood of curious privilege, she now writes and teaches in the Pacific Northwest.

Her writing is deeply feminine, deeply female, and is considered by the author and her following to be deeply feminist. Some feminists recoil, however, at her florid excesses, the very baroque qualities adored by her fans. Spoiler alert: this chick is not a minimalist. Her detractors call her self-indulgent. She is, in fact, the polar opposite of Hemingway, stuffing every frilled, bursting sentence with a magpie’s clutch of shiny things, piling adjective upon adverb, the more Latinate the better, like layers of a cream cake stacked so high that the center will not hold. What springs to mind is the scene in the film Amadeus, where the Emperor Joseph II critiques the work of Mozart this way: “Too many notes.”

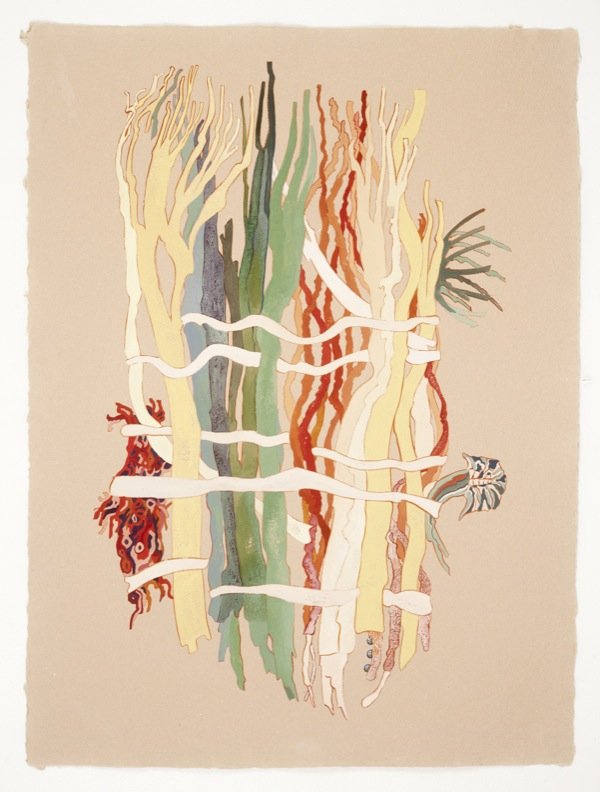

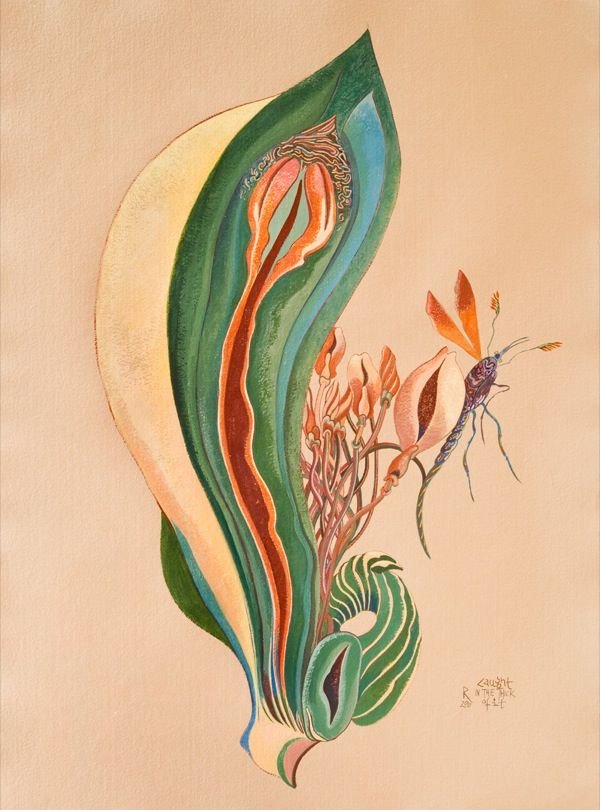

In the movie, a peevish Wolfgang asks which notes should be trimmed, and of course there is no answer. The same challenge would confound any editor wishing to streamline Ducornet. Initially it might seem easy enough to pare down the descriptions, the parentheticals, the digressions, seeking the sleek musculature of more modern-seeing prose, as well as her poetry-- she writes both. She’s also a prolific artist and illustrator. By most recent count, she’s written 26 novels, a half-dozen books of poetry, contributed to numerous anthologies, and illustrated books written by other people -- P.H. Muir’s translation of Beauty and the Beast, for example, and others including Spanking the Maid by Robert Coover, and Horse, Flower, Bird by Kate Bernheimer. She’s called a post-modernist and surrealist by literary critics, sorceress and alchemist by poets of her coven.

But deconstructing Ducornet is no easy feat. Shortening a few sentences and plucking a few of the showier terms may work. But more extensive cosmetic surgery of her work reveals the artist’s secret: it’s not just fluff. What may seem like meringue is simply the skin on a stainless steel superstructure of dazzling strength, strong enough to support all of those plump, pillowy paragraphs and overstuffed, perfumed sentences. Ducornet’s greatest gift as a storyteller is that of artifice. At first, we think she’s no more than a frilly, foofy party-dress. But as we peel away the petticoats, we’re met with toughness -- not just a whalebone corset or Madonna’s black leather teddy, but St. Joan’s flame-burnished armor. Her architecture seems formidable, so academic, so accomplished, so accoladed. But then there is a clap of thunder, a puff of smoke, and like a tent-show tarot-reader, she has hastily folded her tent and we can only watch her small figure scurrying over a low hillside, hurrying out of sight just ahead of the rain. It’s all been a dazzling sleight-of-hand.

Ducornet is always writing about sex,

although you as the reader may not think so at first.

In the world of Rikki Ducornet, teeming with intrigues, moonstruck and spilling over with blood-oranges and orchids, whispered secrets, poisoned jewels, and petty cruelties, a pipe is never just a pipe. Her context is usually some form of the patriarchy, often symbolized by colonial exploitation during the Age of Discovery and the repressive regimes that continue to prevail in its aftermath. In her poem Bees are the Overseers, she writes:

“Power never abandons its funereal mantle, nor its funereal appeal,

yet some continue to mistake the dubious attractions of secular authority for

the natty garments of seduction.”

Her protagonist is always the sovereign imagination which manages to pull free of the magnetic orbit of authority and propriety, only to go recklessly reeling through the stars. In her novel The Fan-Maker’s Inquisition: A Novel of the Marquis de Sade, Ducornet writes about the notorious 18th century libertine in heroic terms, so it’s really no surprise that she doesn’t mind the rough-and-tumble journey required to navigate her literary cosmos. The straight and narrow, she is often quoted as saying, ends at a door made of lead. Only the winding, lost, torturous path leads us back into the garden.

Those of us who like surprises enjoy her capering. Maybe because we know there’s always more. When taken seriously, Ducornet is more than a face-value trickster: she’s an alchemist, concerned with metamorphosis in all of its stages. These instars captured so vividly in the artist’s paintings and drawings as well as writing range from ravenous, pooping caterpillar to death-like dissolution and repose in the chrysalis to exultant escape and flight. She doesn’t steer clear of the messy parts, placing her in the company of Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Dali in terms of easy conference with the grotesque as part of the refinement of self and story.

Ducornet’s trippy lexicon is heavily threaded with references to Gnosticism, which interprets the world as the eternal battle between dark and light. The Gnostics summarized the dualism of existence in feminine terms, casting womankind as the archetype of evil. Her tales also shudder and shimmer with references to classical alchemy, symbolized by the union of feminine Mercury and masculine Sulphur, the lunar and the solar, refined into silver and gold respectively and consummated in the creation of the Philosopher’s Stone. When it suits her, she melds these two quite distinct philosophies into her own hybrid cosmology. An example is her frequent contrasting and pairing of black and white in her stories, symbolizing Gnostic conflict as well as Nigredo (putrefaction, blackness) and Albedo (purification) of primal matter in alchemical terms. (Intriguingly, the Alchemical third step is Rubedo, or reddening, suggestive of the pomegranate’s sweet-sour arils and also the motif of the Snow-White fairytale, red, black, and white.)

This black/white contrast also carries other subtler nuances, including a reference to the Arabic-language poetic traditions of North Africa, a place where the author spent childhood years (Egypt), and returned as a young bride (Tunisia). Erotic poems in this tradition contrast the dark, forgiving night where forbidden lovers steal off to lie together in secret, crushing beds of fragrant herbs beneath them, until the inevitable, harsh whiteness of dawn drives them apart, back to their normal, public lives. In this context, blackness is yielding, fertile and feminine, like the earth that nourishes the pomegranate tree, while whiteness is dry, bitter, and sterile, like the membranes inside the fruit.

Adding frisson is that many of these poems were homoerotic in their use of Arabic pronouns and gendered forms. Literary scholars generally concur that these frankly sexual, yet lyrical poems -- unlike the blunt locker-room talk of Roman Catullus -- found their way into European cultures via the silk and spice routes. The consensus is that musicians often travelled with the merchants, using a song or a strum to help them sell their wares in exchange for a warm meal and a place to sleep. This was, circa the 12th century CE or so, a radical shift, since the only widely available music was liturgical. Calling themselves troubadours,from an Old Occitan word meaning “to compose,” these minstrels shifted the gender forms to be conventionally heterosexual and sang in the local dialects, not the memorized Latin of medieval church music.

These ballads often referenced courtly love, a dynamic centered around a very married, highly visible noble woman and a knight who secretly burns and yearns for her, mirroring the clandestine quality of the Berber and Bedouin originals. Ultimately, the troubadours sang about the love and longing between ordinary people, creating a new kind of folk or pop-music in the form of the European romantic ballad, and mixing in coarse humor (fabliaux and chansons de geste) as a tonic palate-cleanser, to keep things from getting too swoony and dreamy. In this way, Ducornet is a troubadour as well, collecting and collaging language and story for our amusement and enchantment.

Her first four novels map out the four ancient elements of alchemy:

Earth (The Stain),

Fire (Entering Fire),

Water (The Fountains of Neptune),

and Air (The Jade Cabinet).

Her fifth novel, Phosphor in Dreamland, explores light, ether, aligning it with the concept of the intangible fifth element from which we get our word “quintessential.” Defined by these familiar boundaries, Ducornet sets off in search of magic-- all kinds. Like the aristocrats of the 17th and 18th centuries who compiled elaborate wunderkammern (“wonder chambers,” or cabinets of curiosities), Ducornet tacks effortlessly between the fanciful and seemingly factual (one never knows with Rikki), between superstition and science, the sublime and the merely macabre. She is a lifelong student of formal botanical illustration, using the Linnean as reference for her own seething portrayals of mandrake roots, seed pods, sea-shells, mollusk embryos and fossils as talismans and amulets that suggest the work of Georgia O’Keeffe and Judy Chicago-- the latter famously said of her own ceramic creations for The Dinner Party, “Sooner or later, everything starts to look like a vagina.”

This writing is strewn with alchemical symbols, including the planets, the triad of black, white and red, bugs, slugs, snails, reptiles (including the Ouroboros, the snake biting its own tail) and frogs symbolizing the green, primal ooze from which consciousness arises, and eggs, even including a sugar Easter-egg with a cellophane window, are everywhere, Ducornet’s constant reference to fertility and new beginnings.

EARTH:

Her first novel, The Stain, is focused on terrestrial symbols. The protagonist, Charlotte, is born with a birthmark, a stain of her mother’s sexuality. The daughter decides that she contains evil, and must be purified, a process that she attempts to hasten by swallowing broken glass. She enters a convent, and the onset of her menarche triggers a violent cyclone that flattens the valley, much like Dorothy’s head-bump and fever-dream in The Wizard of Oz. The novel ends with the melodramatic death of an exorcist, and a magic hare, the shape of the girl’s birthmark, who appears and is gone in an arc of fire.

FIRE:

Entering Fire, Ducornet’s second novel, dares us to step into the flames of transformation. Here, the action turns overheated as the reader is ferried into the heart of las Amazonas where we encounter hell on earth. In this tale told almost entirely through male characters, sparking the ire of many feminist critics, we witness life as a constant bonfire. A spoiled Parisian son burns his father’s library, gleefully equating the action to the ovens of the Holocaust. The son’s father then exiles himself to South America, where a child takes her first steps over a bed of smoldering coals, and he meets the love of his life, a young Indigenous woman chewing on a smoking, newly roasted iguana. When an evil rubber tycoon murders the inhabitants of the local village, the lovers burn the village to the ground as a way of honoring the dead. In the end, the native woman kills the villain with the fumes made by burning poison ivy.

WATER:

The element of deep emotion, Water, themes the third novel in the tetramorph, The Fountains of Neptune. Here, Ducornet creates a mirror-like world of reflections and memories, contexted first by Swan Lake and a boy’s search for his dead mother, Odile, the malicious black swan of the classical ballet. Diving after a watery image of his mother, the protagonist plunges into the depths of the lake and enters a half century-long coma as a result. A chilling motif is a pickled human fetus in a jar of fluid, a commonly collected component of the wunderkammern; the son longs to reduce himself down into the preconscious, enclosed state of prebirth, where he and his mother were inseparably bonded. Wet weather defines the story’s locale, and aquatic creatures fill the pages of place where we find “port and sky and sea all smeared together like a jam of oysters, pearl-gray and viscous.” In the last moments of the story, the sea gives up its dead, the past gives up its secret. A love-triangle set the protagonist’s narrative on its murky path. His father was strangled and thrown overboard by his mother’s lover. In return, Odile and her lover were bludgeoned to death by the local townspeople, memories that the story’s protagonist has repressed since infancy.

AIR:

The fourth novel in the series, The Jade Cabinet, is the deeply bizarre story of a two Victorian daughters who live in the world of iridescent beetle’s wings, vapor, and air. Their father is an entomologist, and a family friend delights them by making paper birds that take flight over the steaming tea kettle. As is often the case, the novel’s villain is a crass industrialist who makes his fortune by exploiting Indigenous lands and people. He persuades the father of the girls to trade the younger daughter, Etheria, for a priceless piece of jade. He then extinguishes the girl by crushing out her essence, paving over her wild, damp, mossy garden where fabulous insects hum and shimmer amidst lush foliage. Through magic, Etheria literally makes herself vanish into thin air and escapes.

LIGHT:

The fifth novel in the series, Phosphor in Dreamland, carries us into the quintessence, light. Here we encounter many of Ducornet’s standard stock characters: the curious, deformed child, the deluded scientist, the oppressive colonials. Along the route, Phosphor, the club-footed, cross-eyed titular character, invents photography, mercurial silver being the record of memory.

In synopsis, Ducornet’s story-outlines read like bad telenovelas, and their flamboyance is indeed a defining quality. Unfortunately, the deliberate garishness of the author’s prose style causes many to abandon ship prematurely. In addition to her tireless curiosity regarding esoterica of all kinds, her detractors miss the fact that Ducornet offsets the strangeness of her stories with rollicking humor and a bawdiness that would have made Chaucer blush. For instance, by the middle of her first novel, The Stain, the turgid characters are fully at play in vaudevillian slapstick. In Chapter 17 while seated at the dinner table, the Exorcist removes his boot and pleasures Mother Superior from below with the probing of his big toe. The single-entendre table-talk that conceals the encounter is worthy of, perhaps, Mel Brooks. By Chapter 18, the Good Mother is on her knees before her crucifix, confessing “I am plagued with base longings of voluptuous intent!” Ducornet observes, “Until now, there had only been the Holy Ghost-- who once in a dream had entered her womb.

A white dove, plump and well-formed, with a wet, pink beak, he had circled, circled, circled, before settling down upon her-- as on a nest -- in a flash of radiance. She had arisen thrilled to the quick by the plodding of his little yellow feet, the hectic peck-peckings of his little beak, the beatings of his wings…Were not these heavenly caresses enough to fill one woman’s flesh, one woman’s flesh?” When the Holy Ghost apparently refuses her invitation for further consummation (“Come, Little Dove! Little beak! Prick me!”), she and the Exorcist take their mortal coupling to the garden, “…her head pressed painfully against the unforgiving watering can” in the toolshed.

Broad humor is a welcome tonic to the author’s exhaustive erudition, and it’s just one of the amulets -- be it a dusting of Come-to-Me powder, a black cat’s bone, a dried rooster’s comb -- in Ducornet’s red flannel gris-gris bag of tricks. Jumbled and tumbled between her learned prose and breakneck imagination, who can say what entities they’ll conjure next?

All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.