Secret Alphabet

by Victoria Thomas

Lovers of mystery may not like the idea that everything may be reduced to integers, units, clicks, degrees, sequences of dots and dashes.

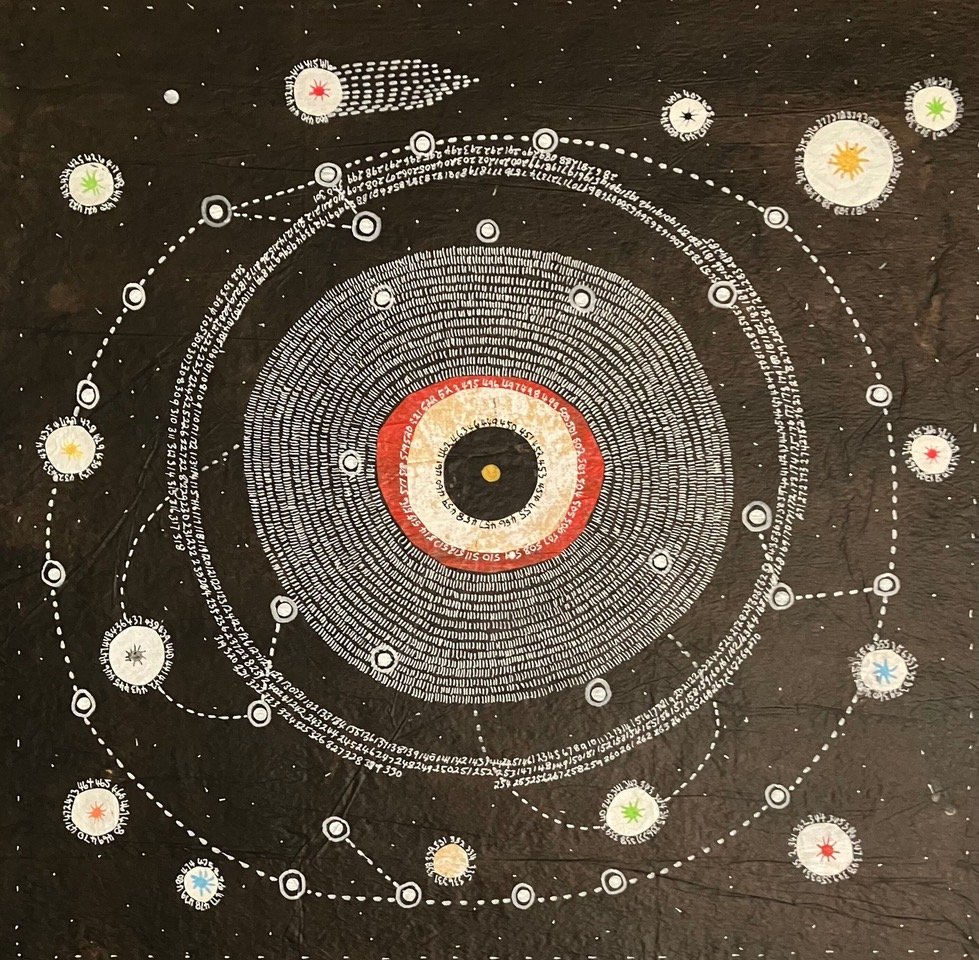

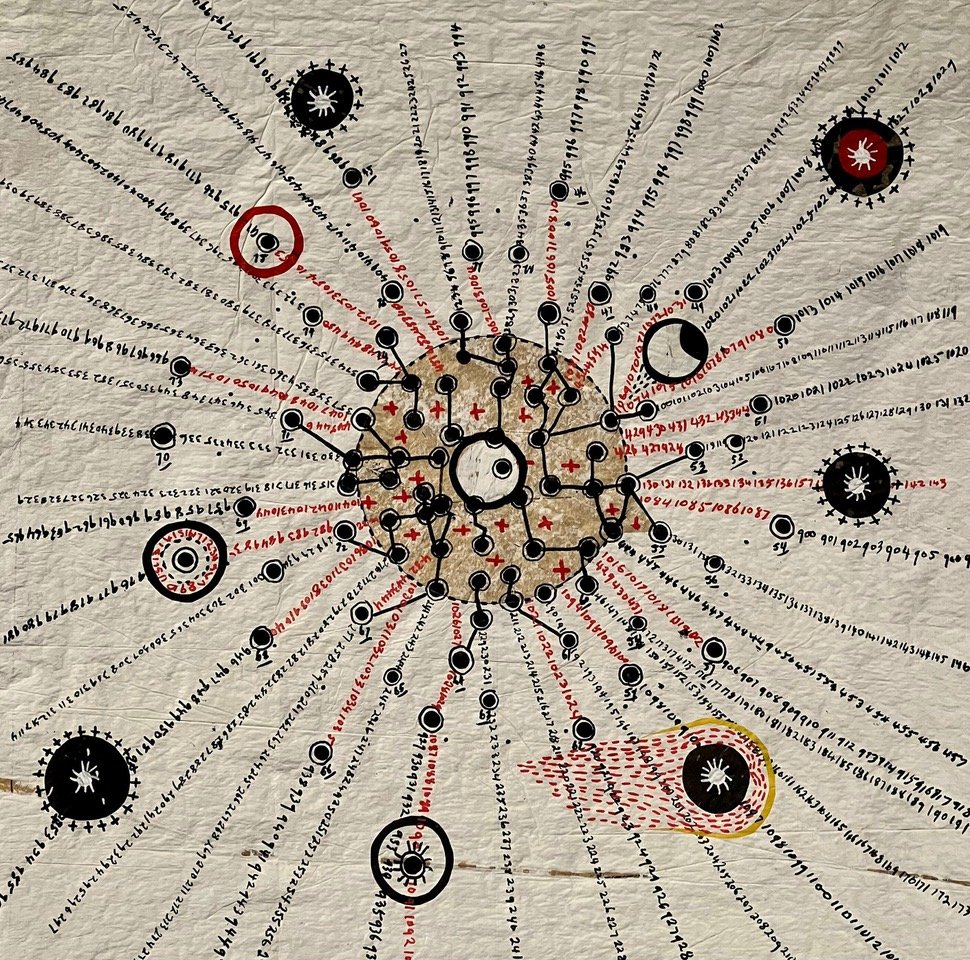

Whether recording the anatomy of the DNA sequence or the murmurings of planets, humans insatiably chart and diagram everything we encounter in an effort to graph our own coordinates and understand our role in an unintelligible universe. Tasmanian-born artist Shane Drinkwater @shane_drinkwater is no exception, except that he creates what appear to be cosmic calendars, maps and charts which don’t explain, but rather provoke.

Soolip caught up with the artist via Zoom on a recent Sunday afternoon at his home in Queensland. The artist is preparing for an exhibition of his work at New York’s Cavin-Morris Gallery opening September 7, which seems to amuse him. “I basically don’t have representation here in my own country,” he says. “I’ve done my time contacting galleries, and was a dismal failure at it. But social media, Instagram, found me.” Modesty aside, Drinkwater’s works on paper and canvas are sought out by museums and galleries around the world.

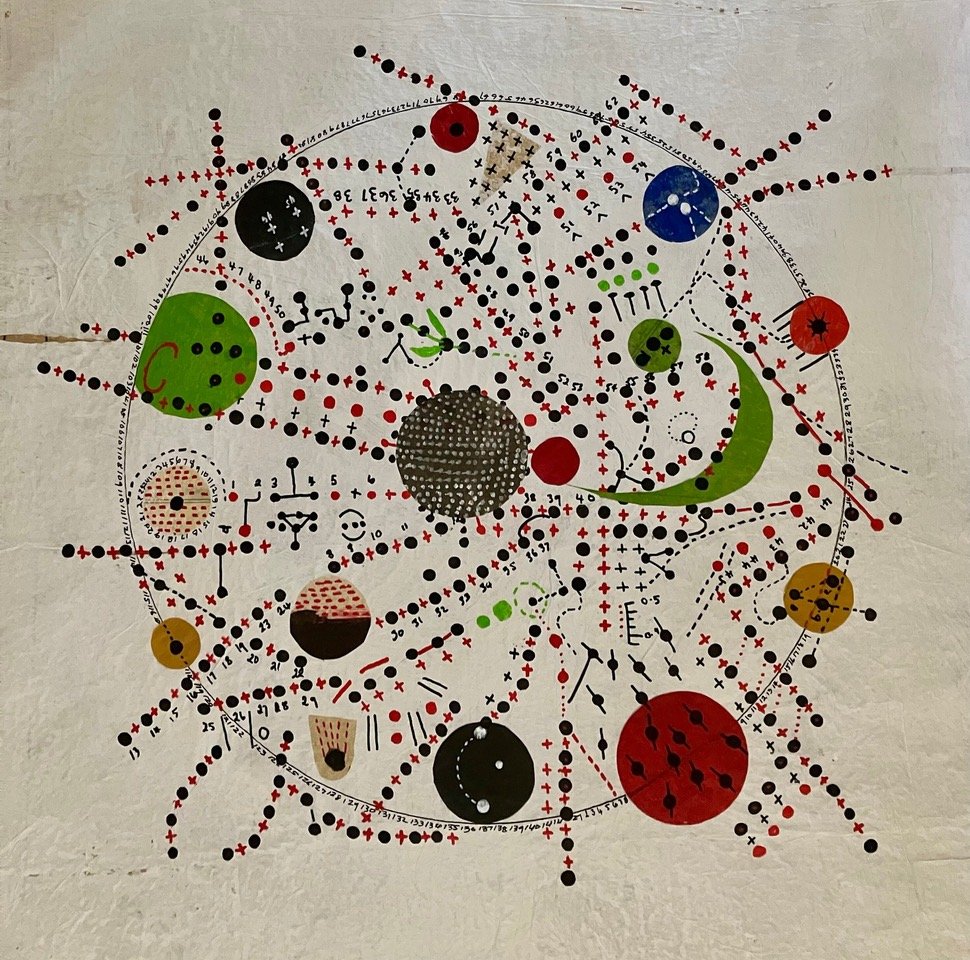

One theory regarding the appeal of his work is that his paintings satisfy the human craving for order and structure. He chuckles at being called “cerebral.” “Actually, I’m dyslexic,” he says. “When I would walk to school as a kid, I’d count every step along the way, count the bricks in a wall, that kind of thing, real classic OCD stuff. Now, I make an effort to not overthink, and not let my brain get in the way when I’m making art.” Math and numbers moreso than words speak to Drinkwater, not in the purely academic way but more in the language of synesthesia. He recalls, “As a child, I had a very strange feeling that colors had numbers and numbers had colors. I can only remember a few: 1, white, 2, blue, 3, green, 4, red.”

His interests include astronomy, archeology and ancient manuscripts although he insists that there is no actual cipher to be cracked, calling this aspect of his work “secret codes of nonsense.” He cites Catalan master Antoni Tápies as source of inspiration, resonating to the Dau at Set (meaning “seventh face of the dice”) movement which translated the conscious and unconscious mind into art, combining symbolic elements of science, philosophy and magic. As a fledgling artist, Drinkwater first explored figurative drawing, and painted “fairly traditional landscapes in oil and acrylic” until he discovered texture. After a five-year respite, he began painting again, imposing new rules upon himself: produce one painting a day -- today, he sometimes produces two per day-- working in a very simple palette (usually blue, black and white), using a small vocabulary of repetitive dots, crosses, and short lines. Gradually, his paintings became larger while still adhering to this minimalist regimen.

In spite of these demanding restrictions, Drinkwater’s self-discipline isn’t harsh. “I paint every day. My studio is this tiny space that’s very chaotic. I like to be distracted while I work, so I begin my day by putting the radio on, and I listen to information on ABC Radio Nation (roughly equivalent to NPR) while I rearrange things and try to tidy up.” He often works on the floor of his studio, explaining that he may have the painting already visualized in his mind before starting. “But sometimes, that goes a bit sideways,” he says, “…in which case, I just go outside with the dog and play for a while.”

The artist’s location in Australia raises the question of dots, a dominant technique in Aboriginal dreamtime art. “There’s no connection,” he says, “although the repetition of patterns may seem similar.” A more personal influence may be the memory of the artist’s mother, who was a seamstress. Today, he buys packets of dressmaker’s paper used to cut patterns as the basis for much of his art, which he dyes to achieve the texture of old parchment. He also collects vintage “sewing tapes” or time-softened waxed linen or cotton tape-measures, which he likes not only for their crisp, tidy numerals, but also because they’re flexible. “They’re very nice and tactile,” he says.

Drinkwater is anything but doctrinaire when engaging with his work. Simple encounters, such as recently discovering a cache of round cardboard circles, may lead to a dizzyingly fast day’s work. “I keep my mind on what my hands are doing by working really fast,” he says. “Although creating gives me great joy, I think now I’m working from instinct, not so much from emotion. I’ve been solidly in the zone now for about ten years. For me, being in the zone means not making mistakes, not judging. In some sense, I’ve refined and almost eliminated the process. Sometimes I have doubts, and I think to myself, this is not gonna happen. Sometimes in the end, something magical takes over. But I can definitely sense when something’s not right.” When a painting doesn’t work, he may “…chop it up and rework it into something else. In this sense, it’s never really discarded or abandoned.”

He states that he doesn’t especially care if others find his work aesthetically pleasing, and that he doesn’t feel that he is “…a real artist or painter.” What, then? “I want the intelligence of my work to be perceived,” he says. He’s non-plussed when gallery-goers ask him what his work is about and what it means. “What does it mean? Give me a break. Everyone wants these instant answers. I tell them to sit back and let their own experience come to them with the answer. This seems to be a very difficult lesson for people to learn.”

His hypnotic sequences of spaces and marks may suggest early computer punch-cards (remarkably derived from the jacquard weaving loom), or perhaps the notched, slotted roll used in a player piano. As is the case with many musicians, he says, “I often have no memory of how I’ve done things. That’s because I’m not actually thinking about it while I do it. I might look at something I’ve done a week later or a year later and kind of scratch my head, as in, how’d I get there?” Neurologists might suggest that, like Mozart who stated that he was merely receiving dictation of notes already written in the ether, Drinkwater is channeling an archetypal, repeating neural saga, or raga, onto paper and canvas. We wonder if perhaps Drinkwater is in fact transcribing the complex notation for the music of the very spheres.

All photos courtesy of the artist.