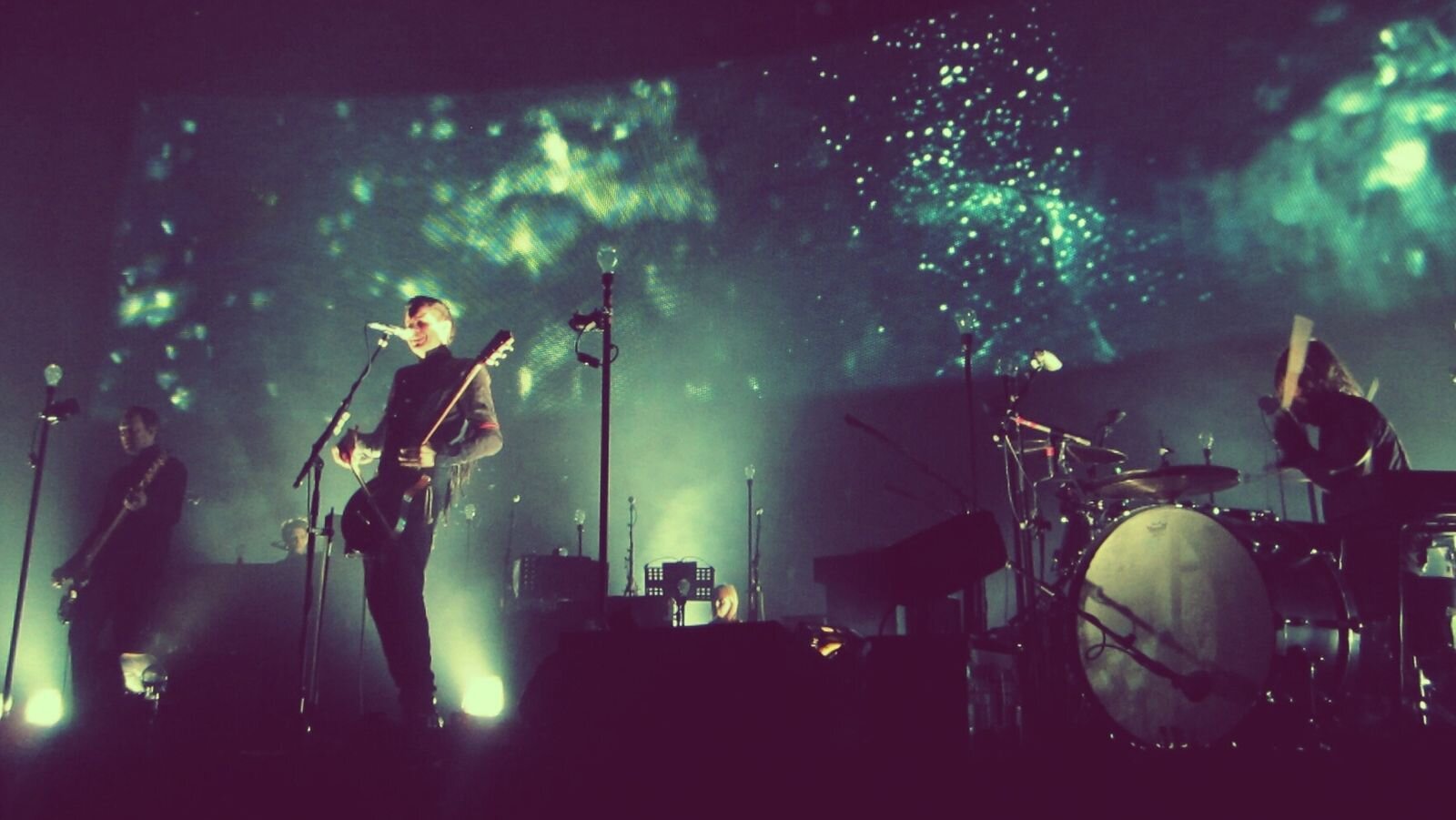

Sigur Rose

by Victoria Thomas

listen as you read…

The band’s name means “Victory Rose” in Icelandic, and is also the name of the frontman’s youngest sister, who was born a few days before the band was formed. Even a casual listen to Sigur Rós is transporting, not only into a song of fire and ice, but into an ambient dreamscape.

It’s easy to see why Sigur Rós is often called “the strangest band in the world”, a title the band’s lead singer and guitarist, Jónsi Birgisson, relishes. The band has enjoyed some mainstream exposure, for the 2010 recording of “Sticks and Stones” and other compositions for the Dreamworks release of “How to Train Your Dragon.” But their sonic sound remains anything but ordinary, 27 years after the band was founded.

The group’s post-rock conjurings of classical and minimal aesthetic elements are defined by Jónsi’s bowed guitar (he uses a cello-bow) and otherworldly falsetto. And what about those lyrics? Many of the song-titles reference a mythic Nordic past, with titles like “Odin’s Raven Magic.” Pieces may include snippets of medieval Icelandic poetry called Rimur, recited by an Icelandic fisherman, and accompanied by a stone marimba. So naturally, when we first listen to Sigur Rós, it’s reasonable to think we’re hearing songs being sung in Icelandic. But more often than not, this is not the case.

As if Icelandic were not obscure enough to most of the world beyond the Arctic Circle -- the Icelandic language, unchanged since the 9th and 10th centuries, is spoken by only approximately 300,000 Icelanders -- Jónsi typically sings in his own invented language that he calls “Hopelandish” (“Vonlesnka” in Icelandic). Hobbit-fans may think they’re hearing J.R.R.Tolkien’s Elvish tongue, and this is also reasonable: according to a 2007 study by the University of Iceland, an estimated 62% of the nation believe that the existence of elves, or huldufólk, meaning “hidden people” in Icelandic, is more than a fairy-tale.

But unlike Tolkien’s well-structured fantasy dialect, Hopelandic has no syntax, grammar, or definitions. It consists of strings of truly trippy, yet meaningless syllables, a spell-like chant intoned under the Northern Lights, gleaming with the steam of Iceland’s newly-active Fagradalsfjall volcano, where the lava-floes, like those far, far away in Hawai’I, are covered with shrines to the unseen beings who inhabit them.

Many of the band’s cuts are performed and recorded without titles, in fact. Sigur Rós uses the gorgeous gibberish or nonsense-singing of Hopelandic – called non-lexical vocables and phonemes by linguists -- as another instrument in their hypnotic, cosmic sound, the melodic and rhythmic elements of singing telling the song-story without the conceptual content of language. This technique is kin to how jazz-singers scat and sing in “vocalese” as invented and perfected by the late, saucy Jon Hendricks. It’s also a traditional form in Irish and Scottish culture, where it’s called “puirt a beul,” or “lilting”, as a verb.

Pure sound has always succeeded in reaching emotive places where language per se often fails. Many opera-goers, for instance, may not be fluent enough in Italian to actually translate and interpret Puccini’s libretto, yet still dissolve into sobs upon hearing the ascending notes of “Nessum dorma.”

To capture the incandescent spatter of their glacial sound, the band sometimes records in abandoned U-boats and empty swimming pools.

In 2019 Jónsi launched into another language without words: fragrance. Like his music, the heart of his olfactory explorings beats deep in the primordial Icelandic landscape. Several years ago, he boiled down and extracted tar from an Icelandic birch tree and began blending, even taking his oils and aroma-chemicals on tour to tinker with in his hotel-room between sets. Of his twin passions, he says, “You create something like music and it is invisible, but still it moves you in some way. It’s the same with scents: you smell something and it moves you. Maybe you can’t understand why, but it triggers a memory or something.”

Jónsi’s descriptions of his fragrances read like an ancient rune etched in a beach-stone:

“N.23: Smoke in the air and tarred telephone poles. In the breeze the feminine fountain pine tickles the top of your skull. A beached whale is about to explode.”

“N.54: Fresh coat of varnish on a wooden shed. Uprooted moss, wet dirt and vetiver roots. Burnt car tires on hot asphalt and dry patchouli. Heavy, slow-drying oil painting. Icelandic alpine fir, footsteps in frozen grass and salt liquorice. Dirty leather, animalistic musk and ammonia.”

The artist uses his own body as a canvas for his olfactory experiments, and doesn’t wear commercial scents. Instead, he may spray himself down with a pure plant distillation or a pure chemical base, to road-test the sensory experience.

So whether sampling Jónsi’s fragrances, now marketed by his sisters in Iceland at a bricks-and-mortar location in Reykjavík called Fischer, or immersing yourself in the ghostly sound-bath of Sigur Rós, start by closing your eyes and taking a deep, deep breath.

All photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.