Mad Pursuit, Struggle to Escape, Wild Ecstasy

by Victoria Thomas

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:

What leaf-fring’d legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals, or of both,

In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

Excerpt, Ode on a Grecian Urn

John Keats

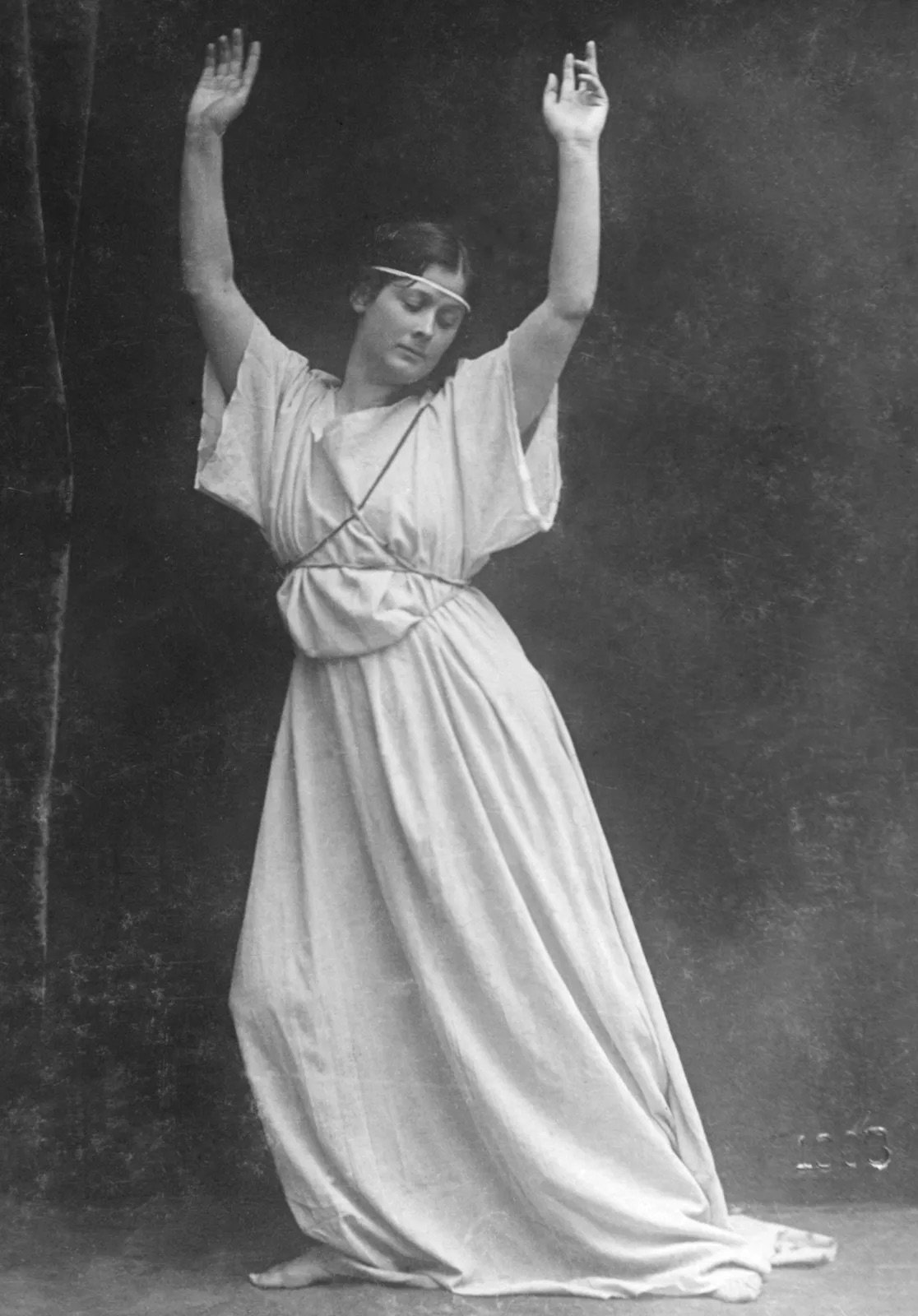

Long before her gruesome death at age 50 in 1927, modern dance visionary Isadora Duncan was a laughingstock.

A young George Balanchine saw Duncan perform in the 1920s and commented to The New York Times that Duncan was “…a drunken, fat woman who for hours was rolling around like a pig.” Noting that Duncan died when one of her trailing trademark silk scarves became snarled in the wheel of a moving convertible and wound around the axle, jerking her from the cab and dragging her along the cobblestones before breaking her neck, Gertrude Stein remarked “Affectations can be dangerous.”

One imagines the hard laughter of the Greek gods joining the scorn of Duncan’s earthly detractors. As a self-styled neo-pagan, Duncan defied all prevailing social mores under the auspices of inspiration by the ancients. Although she rejected the idea that her performances were literally Greek in origin, or literally anything at all, the Hellenic references are clear. She also rejected the media labels of nymph or fairy, maintaining that her utterly improvised dance esthetic was instead the expression of woman-ness at its most natural, in bare feet. She protested, “From the mystery of the Parthenon, the frescoes, the Greek vases, and the Tanagras came my dance—not Greek, not Antique, but in reality the expression of my soul moved to harmony by beauty.” While willing to pose for still photographs, Duncan refused to let early filmmakers capture her movements, stating that filming the movement would make it a dead experience, and adding the technology was too crude to do her art form justice (she was right). Also, given Duncan’s instinct for self-promotion, she may have hesitated to allow recording that might facilitate copycatting.

Ballerina, you musta seen her, dancin’ in the sand.

Elton John, Tiny Dancer

Like her contemporary Virginia Woolf, Duncan “…was aware of an undeniable sadness at the back of life, yet alive to every tremor and gleam of existence,” as Woolf wrote of the Hellenes in her essay On Not Knowing Greek. Feeling the call of the wine-dark sea, Duncan often danced on the beach. Describing her dance improvised to Wagner’s Tannhäuser, Duncan wrote "I am only able to give you a vague indication,... of what most dancers will be later on-masses rushing like whirlwinds in rhythms caught up by mad waves of this music, flowing with fantastic sensuality and ecstasy. Can all this be expressed? Can these visions be clothed in a manifested form? Why try this impossible effort? I repeat, I do not fulfill it, I only indicate."

With similar reasoning, Woolf maintained that rhythm was more essential to her art than representation, noting that rhythm is “…very profound, and goes far deeper than words.” Describing the process of writing The Waves, Woolf describes that her ideas “…flaunt and fly like the shadows over the downs. I think then that my difficulty is that I am writing to a rhythm and not to a plot. Does this convey anything?" Woolf was determined that her images must "never work out; only suggest" and that she must "break up, dig deep, make prose move—yes, I swear --as prose has never moved before." Although there is nothing to suggest that the two artists ever met, both women were prescient feminists and iconoclasts who shook society to its core, while finding themselves quite fragile in the process.

The early twentieth century formed a stage for Orientalism, exoticism, and thinly cloaked eroticism of all kinds, crowned perhaps by dancer Nijinsky’s scandalous scarf-work in L'Après-midi d'un faune —a prancing, preening, horned and horny he-goat so utterly outrageous in classic ballet’s largely docile menagerie of firebirds and dying swans. Key phrase: “thinly veiled.” Nijinsky and Duncan arrived in the public consciousness around the same time, as the first World War simmered, Prohibition threatened to stop the party, and women fought for the vote while straining against their bound bouffant hair, padded bustles and tightly laced whalebone corsets. And although the rebellious-from-birth Duncan rejected formal dance training as a child and loathed the orthodoxy of the Ballet Russe, her spirit seems kindred with Nijinsky’s defiance.

To borrow a phrase from Nora Ephron, Duncan was no wallflower at the orgy. In the first decade of the 1900s, French fashion designer and master couturier Paul Poiret became as well-known for his decadent soirees as for his sleek kimonos and cocoon coats. His most famous grandes fête, La fête de Bacchus on June 20, 1912, re-created the Bacchanalia hosted by Louis XIV at Versailles. Isadora Duncan, wearing a Greek-inspired frock designed by Poiret, danced on tables among 300 guests as 900 bottles of champagne were consumed.

Her legacy maintains that she walked out of her first ballet class, age 12, after a mere 20 minutes, and soon left school altogether out of boredom. Her mantra even at that early age: “I have my will.” She told a local impresario named Daly, “What’s the good of having me here, with my genius, when you make no use of me?” She soon moved to New York, but didn’t find her public until her move to Europe in 1899, where she quickly packed the house and performed to sold-out crowds. In Duncan’s autobiography My Life, published posthumously in 1927, she writes of her visit to Russia’s Imperial Ballet School, “The great, bare dancing rooms were like a torture chamber. I was more than ever convinced that the Imperial Ballet School is an enemy to nature and art.”

She despised the repressive rigor, the stiff postures, the rules, and the toe-shoes, so she shocked the world by shedding most of her clothing along with any remaining molecule of inhibition. To public gasps of awe, she took to the stage in unchoreographed, entirely improvised moves, barefoot, and clad only in a diaphanous gown, sometimes pleated to suggest the grandeur of the ancient columns she studied in rapture at The British Museum. A persistent source of formative inspiration was Botticelli’s idyllic Primavera, where the goddess Flora and the attendant Graces gambol with Edenic innocence.

Here it must be said that Duncan immediately invited ridicule, and inspired scores of amateurs (lovers of the arts) and earnest imitators. The neoclassical lends itself to parody, then and now. Duncan remains the subject of modern biographies, notably the 1968 The Loves of Isadora, with a breathless Vanessa Redgrave in the lead. In dramas and musical comedies set at the century’s turn, from Ken Russell’s Women in Love to Funny Girl and The Music Man, ladies of even the most proper social standing find the call of the panpipes irresistible, and don gauzy togas, sheer tunics, laurel wreaths, diadems, and oracular eye makeup after Duncan’s example. For instance, a memorable moment in Russell’s 1969 rendering of the D.H. Lawrence classic finds actress Glenda Jackson as Gudrun surrounded by curious cows. Her response is equal parts Isadora Duncan and Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, the latter being the founder of the kinesthetic dance method known as eurhythmics (before they were a rad British band). Ever-cool under pressure, Jackson calms the restless herd by humming an old hymn accompanied by a few goddess-y gestures. A jab at the lofty sincerity of the era’s most controversial dance icons? Perhaps. Like Lawrence, Duncan dabbled in hypnosis and believed in what was then called animal magnetism, also known as mesmerism (named for Dr. Franz Mesmer), an invisible electrical force possessed and shared by all living things.

Duncan’s success was nearly as painful as her tragic end, generating a life littered with loss and trauma along with celebrity, glamour, and delicious shock-waves arising from every aspect of her life. In a public setting (of course), she famously bared her breasts and waved a voluminous red scarf to proclaim her alliance with the Bolshevik movement. She made no secret of her freewheeling sexual habits which included female partners as well as prominent male lovers, each of her three children being sired by a different man.

She married a (male) Russian poet, Sergey Yesenin, who was 17 years her junior, even though they shared no common language. The union branded both Duncan and her new spouse as Russian spies, perhaps the only unwelcome publicity Duncan received. Spoiler alert: things didn’t go well, and Yesenin returned to Russia where he took his own young life.

It's tempting to indulge in armchair analysis of Duncan in regard to her view of men. She was born into a middle-class family in San Francisco, to a resourceful but dishonest father who earned a good living as a newspaper publisher, real estate broker and banker, embezzled clients’ money, and fled in disgrace. Duncan’s mother, a piano teacher, divorced her husband, who was also a serial adulterer, and took some solace by reading aloud passages from the writings of atheist intellectual Robert Ingersoll. Ingersoll’s radical views may have further soured young Isadora Duncan on the idea of conventional marriage, which she found as tedious as traditional dance.

Duncan began teaching her unique approach to movement to neighborhood children at age 10. By age 12, she and her older sister Elizabeth attracted large classes and earned enough money to support their family. Later, Duncan formed her own dance academy and directed a troupe of young girls she called her Isadorables. Her many trysts produced two children initially, daughter Deirdre conceived with an influential married theatre producer, and her son Patrick resulting from a liaison with the married heir to the Singer sewing machine fortune. Paris Singer bought Duncan a hillside property overlooking the Seine which, with the usual Greek irony as well as tragedy, would be the site of her life’s cruelest heartbreak in 1913. Driving the children and their governess home, the car stalled on the incline. The chauffeur stepped out and cranked the engine, but before he was able to return to the wheel, the car slipped down the bank into the river below, drowning all three occupants.

The following year, she sought comfort with sculptor Romano Romanelli, and happily believed that the resulting pregnancy signaled the soul of one of her lost children returning to her in new form. But in 1914, she birthed a son who lived only a matter of hours, and Duncan’s star began to fade. Cruel notices, a trail of unpaid bills and abandonment by friends followed. A late-night joyride with a dashing beau in Nice – an intoxicated Duncan is said to have crowed “Adieu, mes amis. Je vais à la gloire!" or "Farewell, my friends. I go to glory!” or "Je vais à l'amour" or "I am off to love, " depending on the source, as they motored off – ended her life with a violent twist of fate. But her legend burns on in the collective imagination.

Duncan’s influence and vision persist in every aspect of contemporary dance, including the traditional ballet she despised. In an ebullient mood, she wrote “From all parts of her body shall shine radiant intelligence, bringing to the world the message of the thoughts and aspirations of thousands of women. She shall dance the freedom of woman. O, what a field is here awaiting her! Do you not feel that she is near, that she is coming, this dancer of the future! She will help womankind to a new knowledge of the possible strength and beauty of their bodies and the relation of their bodies to the earth nature and to the children of the future.” To know of Duncan’s life, in spite of all of its grief, trouble, and shadows, is to know the millennia-old joy in the innate nobility of the natural body, perfectly free, as gifted to us by the mighty gods themselves.

All photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.