HENRIETTE NEGRIN: More Than His Muse

by Victoria Thomas

Our story begins two and a half millennia ago, in Delphi, Greece.

The year is about 470 BCE, and the medium is bronze in the form of a nearly 6-foot, standing chariot-driver. We can only marvel and hope that we will age as gracefully.

Although his left arm is entirely gone and his right hand grips the reins of a missing chariot, his hair is perfect, the clipped waves of his coiffure held snugly in place by a headband animated with the classic Greek key meander design. Tighter curls form at his temples, perhaps activated by sweat under the blazing Greek sun. And his garment, forming fine pleats from raglan shoulder seams, descending to his bare feet in a swoop of gently undulating folds, seems almost palpable to the skin of a viewer. The final amazement: his inlaid glass eyes, intent, alert and eternally youthful as he guides his phantom vehicle, are still fringed with eyelashes of silver inlay.

Historians speculate that the Charioteer of Delphi, or Auriga as he is also known, probably cast in Athens to commemorate a tyrant’s victory in the Pythian Games of 478 BCE or 474 BCE, originally met the world with four equally detailed cast bronze horses and two groomsmen. While the charioteer’s contemporaries typically were melted down for their raw materials, this sculpture was preserved under a fortuitous landslide which preserved it. Perhaps surprisingly, it was a gaze back into the deep past which inspired a modernist fashion revolution at the turn of the 20th century.

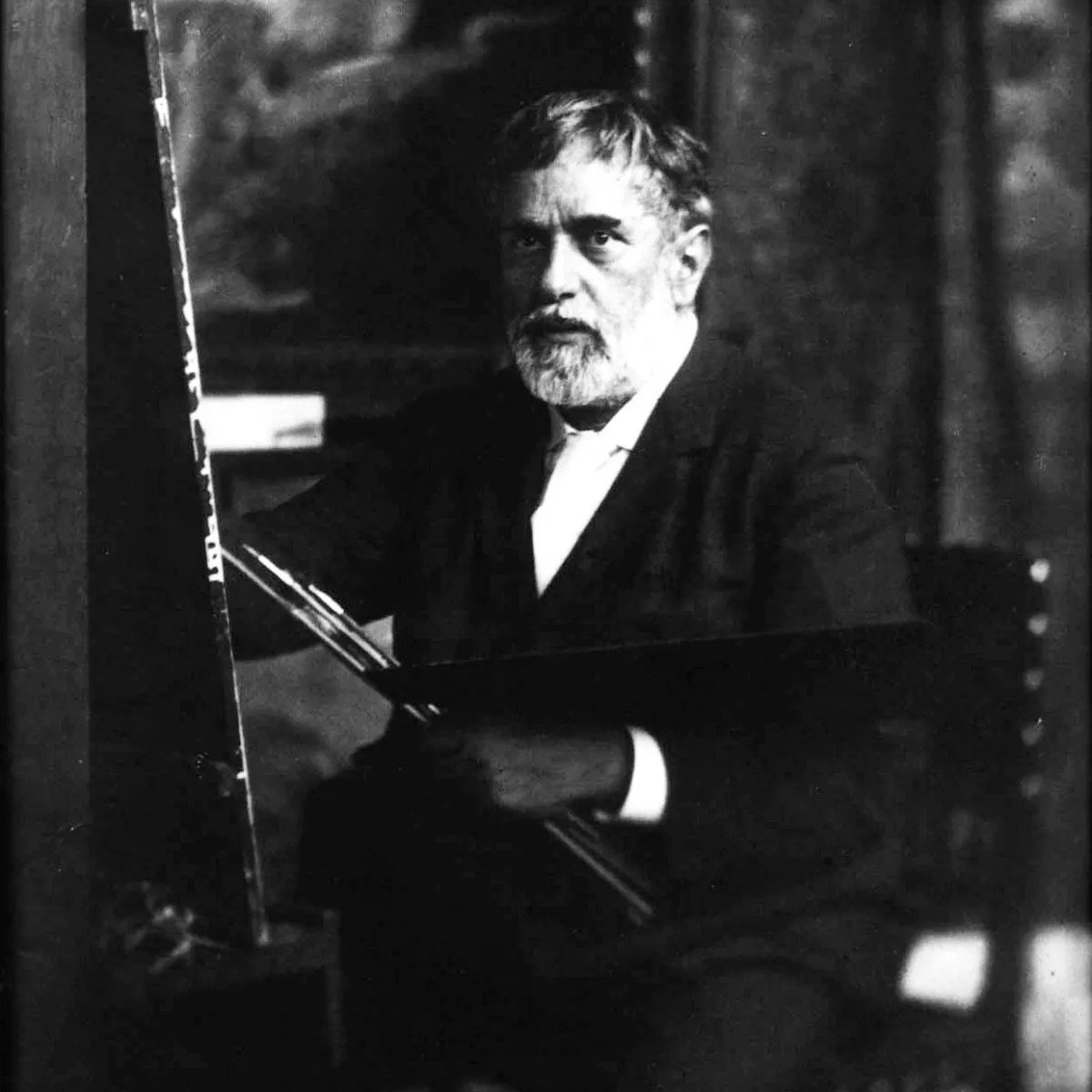

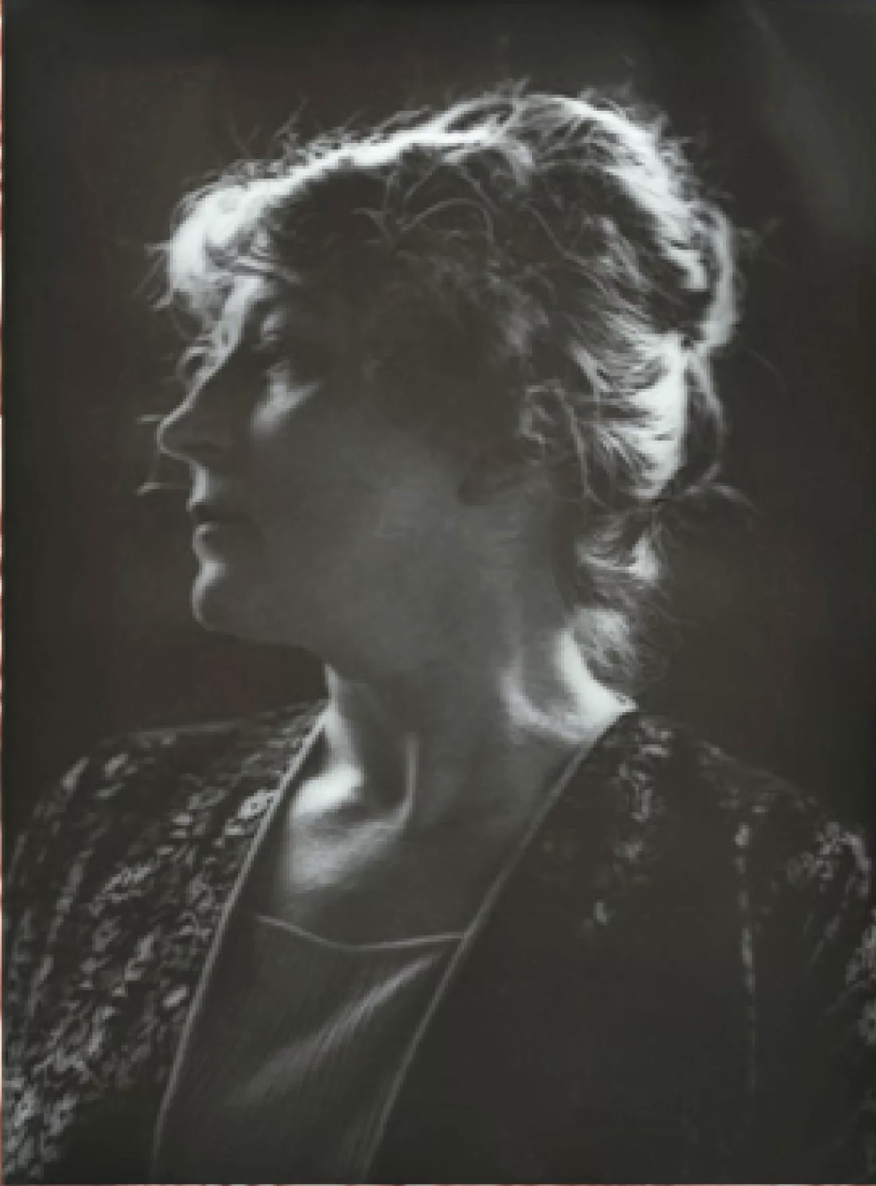

The creator was Henriette Negrin, also known as Adèle Henriette Elisabeth Negrin, occasionally spelled Nigrin, and Madame Henriette Brassart, a name less familiar than that of her husband: Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo. The inconsistencies in the spelling of her name reveal a far greater socio-cultural gap.

For decades, Henriette, a fetching 25-year-old French divorcee when she met Fortuny (his mother vigorously disapproved), was dismissed as merely his “Muse” when in fact she was his co-creator.

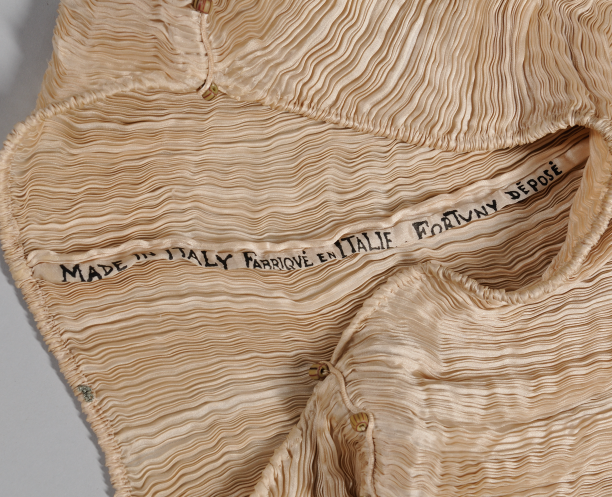

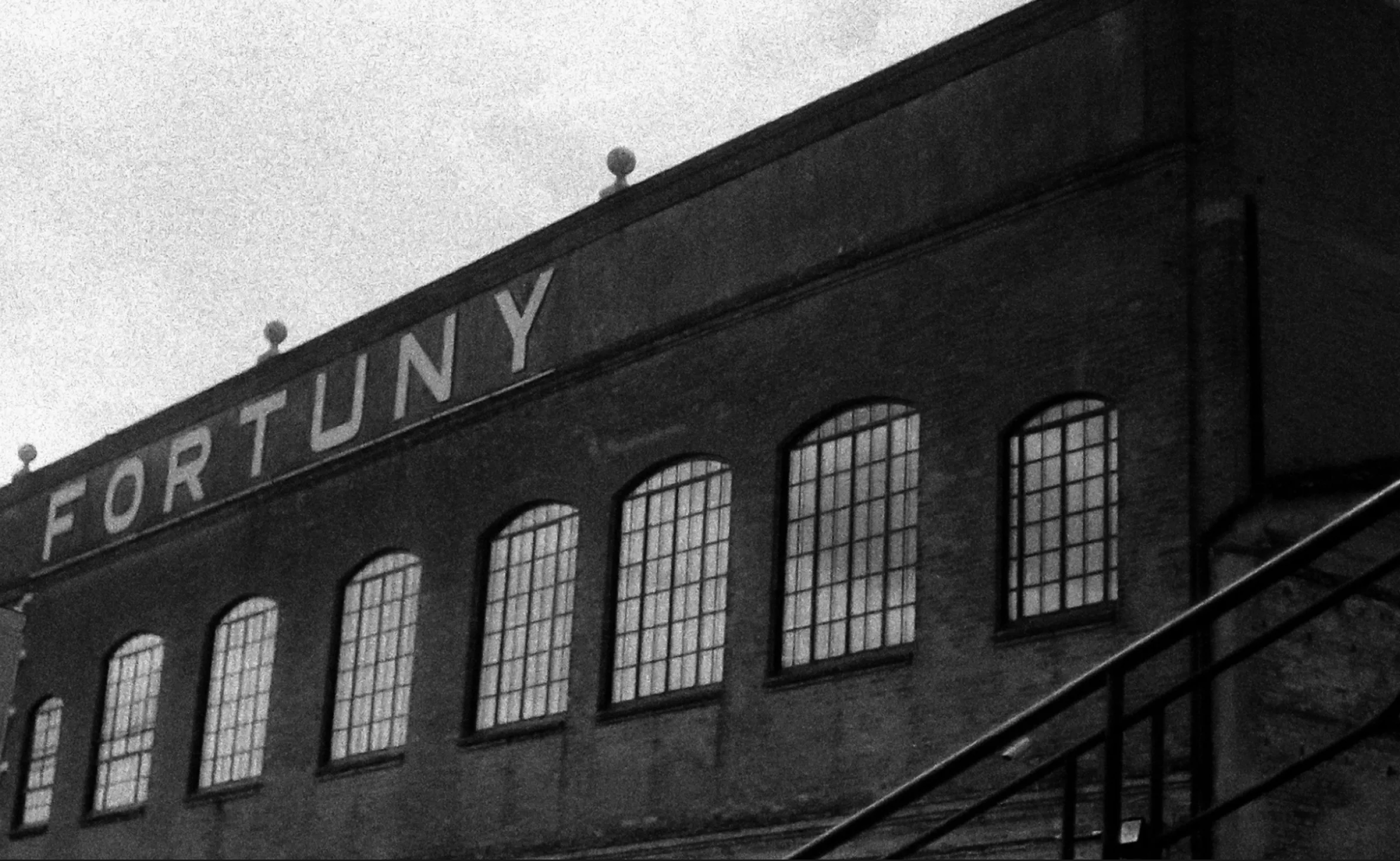

The Fortuny name will forever be associated with pleating which referenced the ancient world – the Egyptians mastered the technique even before the Greeks -- but in fact this iconic (and iconoclastic) garment, the most successful in the Venetian design house’s laureled history, reflects the sensuous genius and technical acumen of Negrin. She called it Delphos. Inspired by the Auriga statue uncovered in 1896, the Fortuny atelier debuted the sleek, columnar Delphos gown in 1909, liberating the feminine body and mind in ways that at the time seemed unimaginable.

The new century was hurtling toward chaos, at least in the sense of disrupting the past. As always, perhaps the most telling record of this is with women’s undergarments. Clothing at the fin de siècle was oppressively structured, perhaps reflecting the West’s increasing desperation in clinging to a crumbling society and need to insulate itself from the coming crises. An exaggerated hourglass shape was the desired female form, and this required formidable manipulation of a woman’s normal contours. The whaling industry provided the baleen (keratin jaw-ribs) that gave corsets the required S-shape. Fashionistas will recall the scene from Gone With the Wind where Scarlet refuses to eat, and is told to “Jest hold on and suck in” as Mammy firmly laces her into the corset that will give her a coveted waist measurement of under 20 inches.

Steel stays later replaced the more flexible whalebone, making the prospect of dressing even more punishing, as any contemporary extreme “waist-trainer” will confirm.

It's essential to understand what lies beneath in order to appreciate the impact of the Delphos gown. In addition to the corset, women of the century’s turn padded and boosted their bottoms with bustles, and even pumped up their chignons and pompadours with frizzettes or “hair rats” made of wire and human hair for additional height and mass.

This artifice would have appalled any self-respecting Athenian who, while perhaps vain, turned to the naked human form as proof of our species’ divine origins. It seems likely that Henriette as a radical denizen of the Belle Epoque would have felt the same.

The pleated gown which captivated the design team was quintessentially Greek, used consistently across many genres and eras of classical sculpture, especially associated with depictions called Kore and Kourous, idealized portrayals of nobles in the guise of either Aphrodite or Apollo. The most famous aficionada of the modern Delphos gown was the boundary-breaking dancer Isadora Duncan, who, true to the naturalistic Hellenic ethos, scandalized the world by visibly eschewing lingerie of any kind beneath her semi-sheer, flowing gowns. The “Divine” Sarah Bernhardt and Clarisse Coudert, the latter the wife of the publishing mogul Condé Nast, were also passionate devotees of the Delphos and other Fortuny creations.

Henriette originally devised the Delphos from four or five panels of silk satin or taffeta, hand-pleating the panels with an estimated 450 folds in the place of darts and other tailoring. The neckline and sleeves were made adjustable by sliding Murano glass beads. The beads also were used as weight, to drape a neckline, for example. The gown was sometimes worn with a beaded belt, or left to hug the hips and breasts unobstructed.

The initial prototypes inspired by the charioteer, who was undoubtedly the teenaged son of a local aristocrat, mimicked his folded chiton by hand-sewing narrow width of pleated silk together to form a sinuous tube that could expand and contract at stress-points, rather like an accordion. The effect was fluid and gently clinging, almost as if the garment were wet, like Aphrodite emerging from the sea, but not restrictive. While the Egyptians and later the Greeks made their pleated garments from substantial flax, linen or cotton, the choice of gossamer silk for the Delphos added a luxurious suppleness and a nod to the Orientalism that was de rigeur. Similar to the “broomstick” India-made gauze skirts we find today, the Delphos was intended to be wound into a loose knot for pleat-preserving storage, much as one would wring out wet laundry.

Husband and his future wife soon patented their pleating machine on June 10, 1909. A translated patent excerpt from the Office National de la Propriété Industrielle reads:

“The dress consists of a robe, open both at the top and at the bottom, whose width can be equal to its length, widening or narrowing from top to bottom or at various points, in accordance with the general appearance and aspect one desires to give to the dress. The fabric can be smooth or pleated; this detail is an independent invention.

The upper section is laid flat so that the two edges are level and these are then fastened at points D and E in whatever way one decides; an opening in the center forms the neckline, two lateral openings are for arms through with, in between, two openings whose edges are laced together. Between the lateral points E and G strings are attached obliquely to adjust and modify distance X which determines the bottom of the sleeve in accordance with the size and height of whoever is wearing the dress. These strings are on the inside of the dress so as to be invisible.”

Mariano included a hand-written note reading "This patent is the property of Madame Henriette Brassart who is the inventor. I submitted this patent in my name given the urgency of filing.” (Brassart was Henriette’s maternal familial name, as the couple was not yet legally wed.) Although we do not presume to truly know the dynamics of the relationship, this much is clear: had a woman filed for the patent, French authorities at the time would have instantly discarded the application.

Rather than structuring a garment to contain and enhance the body’s contours, the Delphos gown expanded and contracted effortlessly to mold to the wearer’s natural shape. Historical sources suggest that the Delphos was a tea gown to be worn in the afternoon, meaning at home. However, period photographs show Henriette wearing the gown and similar prototypes with gloves, suggesting that its creators may have intended it as more formal evening attire to be worn in public– all the more tantalizing since it was made to be worn with only the flimsiest undergarments, if any.

The Delphos may be significant in that it liberated daring women from centuries of constricting, constructed clothing. This shedding of propriety defined the freewheeling flapper chemise a decade later. When Mariano died on May 3, 1949, the House of Fortuny stopped producing Delphos gowns, at the request of Henriette. She wrote to Elsie McNeill Lee, her American distributor, “…Regarding Delphos, after mature consideration – and this is why I have been slow to answer – I have irrevocably decided to cease all commercial production. Similarly, given that these garments are of my own creation, even more than any other, I desire that no one else take them over, and thus to the sale of the Delphos we must apply the words 'the end.'”

And yet, it’s not the end. It may seem ironic that, in order to unleash the modern woman into the 20th century, Henriette Negrin looked back, not forward. Just as both Industrial Revolutions had begun to undo the old order, Negrin took inspiration from a time long before steam-power and the thousand innovations that this single innovation would spawn. Perhaps sensing the collapse that approached in the form of World Wars and economic catastrophe, her senses collected an image reminiscent of facing into the last sunset of a summer’s passing, a brief moment when the world seemed still, bathed in crepuscular tenderness, and altogether whole, perhaps for the final time.

All photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and NYPL Archives.